An innovative study on birth control, published in the New England Journal of Medicine Oct. 2, was reported with such headlines as, “Free, long-acting contraceptives may greatly reduce teen pregnancy rate.” The three-year study of 1,400 teenage women who were offered various contraceptives at no cost showed that those who chose birth control pills, patches or rings were 22 times more likely to become pregnant (during the study) than those who chose implants or intrauterine devices (IUDs).

Pediatricians and gynecologists met the news with great enthusiasm, since it demonstrates that IUDs can be safely and effectively provided to teens and adds to birth control options for young women. IUDs are thus included in new reproductive health guidelines for teens from both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

As a women’s healthcare provider, I was thrilled by the news, but for different reasons. IUDs are one of the most effective contraceptive choices that are controlled by women, overcoming the challenges of condom negotiation that many women are unable to navigate. Having the “condom talk” with a male partner is particularly difficult for those women without social or economic capital—those in violent relationships or dependent on partners for food, shelter or economic security. A condom requires men to be complicit in pregnancy prevention, whereas IUDs empower women to make their own reproductive decisions. Because IUDs are long-acting, they also alleviate the burden for women of having to make an active decision about pregnancy prevention every time they have sex.

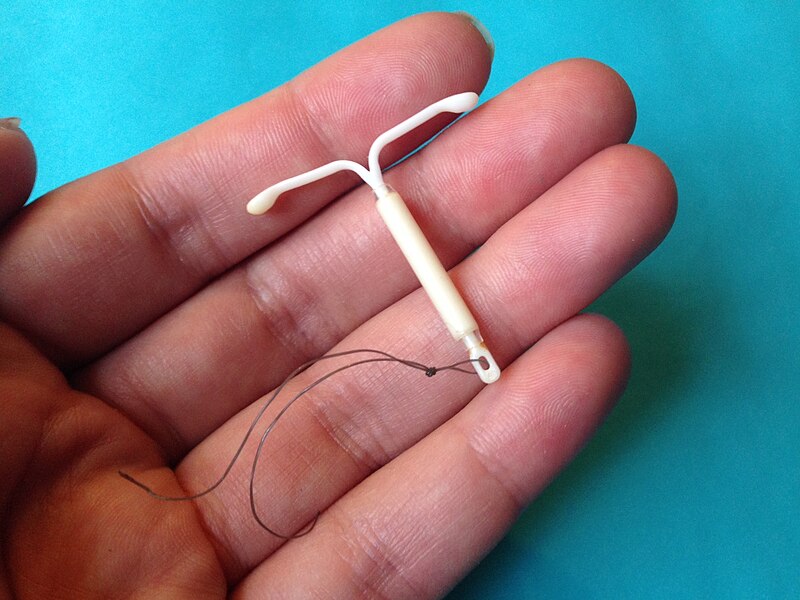

But my enthusiasm about the efficacy of IUDs is tempered by realism. One major problem with IUDs is access: They require a healthcare provider competent in insertion procedures, a skill set currently limited to gynecologists and some family physicians. Moreover, the women most needing effective pregnancy prevention tools are often those marginalized from healthcare providers by lower socioeconomic status, racial or ethnic group and underinsurance.

In spite of the findings of this clinical trial, it is also not likely that, in the current political climate, IUDs will become widely available for free any time soon. While the contraceptive coverage requirement of the Affordable Care Act guarantees greater access, it is still hotly contested in places like Colorado, where it was so central to the midterm U.S. Senate race that the incumbent was dubbed “Senator Uterus.” The controversial issue under debate is whether hormonal forms of birth control, including IUDs, violate “personhood measures” that define life as beginning at fertilization. In the meantime, access to IUDs is limited by cost. As politicians continue to debate the ethical implications of the contraceptive, women are still forced to shell out up to a thousand dollars for this promising intervention, a price not feasible for many.

But even if cost and availability issues were overcome, IUDs do not make sex “safe.” While they effectively prevent pregnancy, as the recent study demonstrated, they offer no protection against sexually transmitted infections (STIs) such as HIV, herpes, chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis and human papillomavirus (HPV). For young women, the consequences of these infections can be significant. In comparison, the condom—despite its many shortcomings—is the only effective prevention measure widely available in the current medical landscape. Condom-less sex still has very real public health implications, since people can continue to unwittingly transmit infections to their sex partners if they don’t use barrier protection.

When people burn out from safe-sex messaging and stop using condoms, we witness resurgence in rates of syphilis and other STIs. According to recent CDC estimates, 1 in 4 sexually active adolescent women presently has an STI, and half of all new STI cases each year occur among those 15 to 24. There continue to be 50,000 new HIV infections every year in this country, the majority of which are transmitted through sex. Twenty-six per cent of new HIV cases annually are among people ages 13 to 24. Promising new prevention technologies, such as preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and vaccines, can prevent HIV and HPV infections respectively, but they only address these two STIs and are available to a select, high-risk subset of the population. I fear that as we spotlight IUDs as the contraception of choice for many young women, the STI prevention benefit of condoms will be ignored.

The women I care for in my HIV clinic are living the consequences of condom-less sex. An IUD may have averted some of their complicated pregnancies, childbirths and childcare experiences. But an IUD would not have protected my patients against the alphabet soup of other medical issues—HIV, hepatitis B and herpes, among them—that complicate their daily lives and oblige them to a lifelong regimen of medications. Although IUDs are an exciting contraceptive option, until they are coated with anti-infectives as well as hormones I will continue to counsel women that safe sex means using a condom.

Get Ms. in your inbox! Click here to sign up for the Ms. newsletter.