This isn’t the article I was supposed to write.

As the director of health equity at the Roosevelt Institute, I research and write about the health dimensions of race, gender and economic inequality.

But I’m also a mom of three kids between the ages of three and eight.

As the coronavirus has unfolded, I have experienced and analyzed what’s happening in my family, in my community and in the world more broadly. (I will note upfront that I recognize the extraordinary privilege I have to be part of a household where both parents still have a paying job.)

Ten days ago I started writing a hard-hitting analytical piece about the chilling attempts of conservative lawmakers to exploit a global pandemic to erode abortion access. On a normal week it would have been something I could have turned around in a day. But these are not normal weeks, are they?

Most days, writing has seemed impossible. I felt the time slipping away as other people published the piece I meant to write. I missed my chance.

This is just one of the ways I’ve seen the coronavirus reveal the fault lines within many of our homes, in our places of work and in the economy more broadly.

The coronavirus has laid bare many divisions in our society. And, like any serious crisis does, it has elevated the extent to which structural sexism permeates our lives: impacting the gendered division of labor within the home and also shaping what is possible for women, and particularly mothers, in the public sphere.

A quick scroll through Twitter explains exactly what I’m talking about:

My experience certainly isn’t universal: There are many different family configurations operating in different ways during this challenging time.

For me, I’m joined by mothers everywhere in having found myself shouldering the lion’s share of the household labor over the last few weeks: We have prepared the vast majority of the meals, cleaned up our kids messes throughout the day and navigated telemedicine calls with our pediatricians.

We’ve done the majority of the at-home teaching, setting up our own laptops at our kids’ make-shift workstations, so we can serve as teacher and IT technician while attempting to do our own jobs.

We’re often the point of contact for our kids’ teachers: In fact, one mother told me recently that when her child’s teacher emailed the original at-home learning instructions to parents, she only included mothers—but that has since been corrected.

The emotional labor is all-consuming.

For the first two weeks of lockdown, I woke paralyzed with panic about my kids’ physical and mental health, and about my husband and me staying well to care for them.

I was panicked for my mother and her colleagues who are like family to me, all of them laid off when the restaurant they’ve worked at for more than 30 years closed due to COVID restrictions.

I was panicked not knowing how the COVID nightmare would unfold and what we would be when this all ends. I laid in bed with my kids and soothed them when they told me they were scared and sad and didn’t know when they would see their friends and family in real life again. I attempted to dramatically reorganize our daily life to accommodate our new reality.

I know it’s a mark of my privilege that there have been few times when I’ve had to parent from that place of panic. I’ve reflected a lot about how exhausting it’s been to put on a brave face to reassure and calm my children in a time of endless uncertainty while feeling anything but brave.

So many mothers I know have had stark reminders that we can only hold so much for so long. There have been more days than I’d like to admit when I hid in the bathroom to cry between participating in work conference calls and administering Google classroom tutorials.

During lunch last week, after an hour of asking my kids to please not throw a ball in the kitchen, one of them accidentally slammed into me while I was making pasta.

In the grand scheme of things, it wasn’t a big deal—bless them for making their own fun on a rainy day during an abysmal time.

But the internal tightrope that had been growing increasingly taut snapped. I screamed, quickly left the room and fell to the ground against my bedroom door and sobbed. I felt completely unmoored.

And then I pulled myself together and joined my kids for lunch, giving them hugs and loving and comforting them as best I could. Pushing down the panic until it escapes again.

The women I know shouldering a disproportionate burden of the household and emotional labor aren’t doing so because our husbands are misogynistic assholes.

In fact, three weeks ago, most of us—proud feminists and progressives—would have said we shared the burden of parenting relatively evenly. (I say relatively because research shows that, despite couples feeling they have egalitarian relationships, women still do the lion’s share of domestic labor.)

Why then, at times of crisis, do these imbalances emerge?

Because structural sexism is always lurking just below the surface, ready to rear its ugly head and quickly upset any semblance of intra-household gender equity.

Think about how structural sexism plays out in the economy and, as a result, also in our homes.

Women make only 82 percent of what their male colleagues make, and Black and Latina women make 61 and 53 percent, respectively.

Only 24 percent of women have salaries higher than their husbands.

Only 19 percent of all U.S. workers have access to paid family leave, and men are far less likely to take time off than are women.

Studies show that three-quarters of all fathers in professional jobs took one week or less off after their most recent child was born, and that only one in 20 took more than two weeks off after. (Sixty percent of low-income fathers take zero weeks of paid time away after welcoming a new child into their home).

The minority of women who are lucky enough to have time off after childbirth or adoption face an extraordinary parent penalty later on. Women’s earnings drop significantly after the birth of their first child, and they end up earning 20 percent less than their male partners over the course of their careers. There is no comparable salary drop for men.

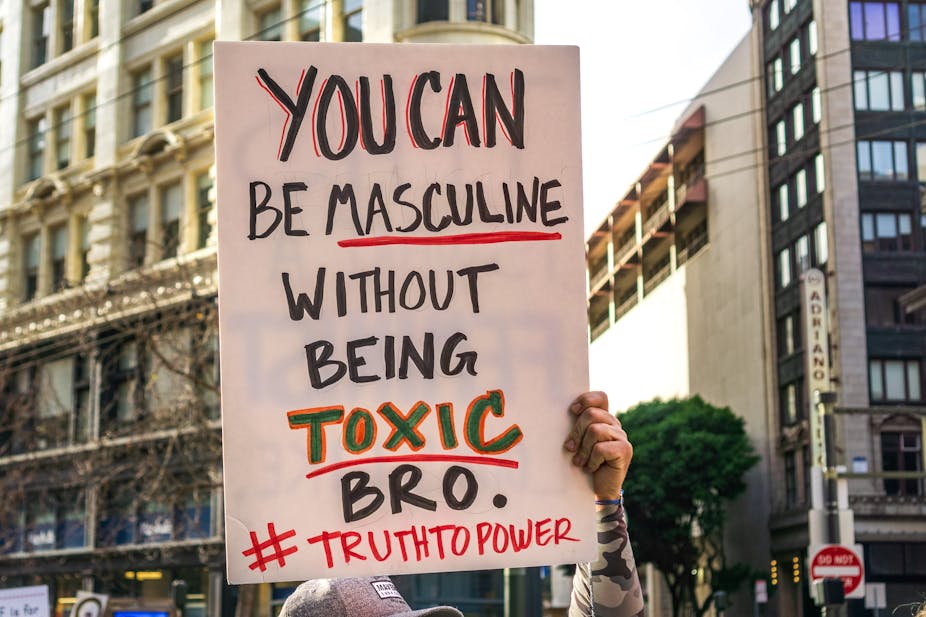

This is of course bad news for women, but it also is bad for men: It locks them into rigid and often toxic definitions of masculinity that make it harder for them to achieve work-life balance and more equally participate in family and home life.

Most men I know want a different reality, but they’re stuck in a system that makes it hard to achieve. This system normalizes a culture where paid leave is a privilege and not a right—which especially hurts lower-income workers who are the least likely to have access to care.

What all of this structural sexism adds up to is that in many heterosexual relationships, mine included, the male partner earns more than the female partner. And in times of economic crisis, when decisions need to be made about the economic security of our families, the job that brings in more money takes priority.

This is particularly true when a historic crisis threatens the stability of the higher earner’s job or industry—as COVID is doing to so many jobs and industries today.

Many women I’ve talked to understand and appreciate this dynamic—in fact, many of us sympathize that our partners are shouldering such a heavy burden of our financial wellbeing. What a weight to carry.

Still, it can be a tough pill to swallow as we attempt to shift our expectations, quell our fears about what this moment means for our own careers and earning potential, and reconcile our new realities with our own feminist ideals.

This imbalance that’s playing out in our homes—and the extraordinary toll that a crisis like COVID is taking on all working parents—significantly impacts how we show up at work and how we perform relative to those who have fewer or no childcare responsibilities.

During the first two weeks of social distancing, mothers in the progressive policy space shared with each other frustration over how hard it was to write and been seen for our ideas. Carving out time to write during these tumultuous days was painfully challenging. In fact, this piece was written in bed long after the kids were tucked in, on a backlit iPhone screen so I didn’t wake my partner.

Lately I find that swirling amidst the toxic storm of emotions that course through my body every day—panic, anxiety, deep sadness, longing and also gratitude—is a strong and steady current of rage.

Rage at the willful ignorance of our national leadership.

Rage that we live in a country so drugged on notions of rugged individualism that we all live in fear of the ways a shift or loss of employment would impact our health and our ability to care for our families.

Rage that women need to hold so much more than our hearts and brains and arms have room for. And that the whole system feels more broken than it ever has.

This is the rage that authors like Rebecca Traister and Brittney Cooper have so powerfully given voice to.

How can we not feel rage when we think about how the imbalances of COVID are unfolding against a relentless backdrop of stark gender inequities and injustices?

Women’s labor is underpaid and underappreciated.

The person making decisions about our lives gets to be president even after admitting to sexually assaulting women, and while he degrades women from the podium on a daily basis.

Women are routinely harassed and assaulted at their place of work.

Lawmakers care more about controlling our bodies than they do about keeping us alive.

The people who literally hold up our economy—on their backs, with their care-taking hands, and on trays held on their shoulders, like my mom—are those who will be most quickly left behind and will pay the price of our government’s negligence for the rest of their lives.

And when we exit this COVID horror show, the world we re-enter likely won’t feel safer or more equitable. In fact, the opposite is probably true.

All that makes it so much harder to adjust to the weight of any imbalances in the scales of our households.

The other day someone asked me how work was going. I joked that my male colleagues are on the path to becoming “COVID famous” while I am learning elementary school math. That would make a good book title, they suggested.

I laughed. And then I cried. Because fuck if I can write a book right now.

The coronavirus pandemic and the response by federal, state and local authorities is fast-moving.

During this time, Ms. is keeping a focus on aspects of the crisis—especially as it impacts women and their families—often not reported by mainstream media.

If you found this article helpful, please consider supporting our independent reporting and truth-telling for as little as $5 per month.