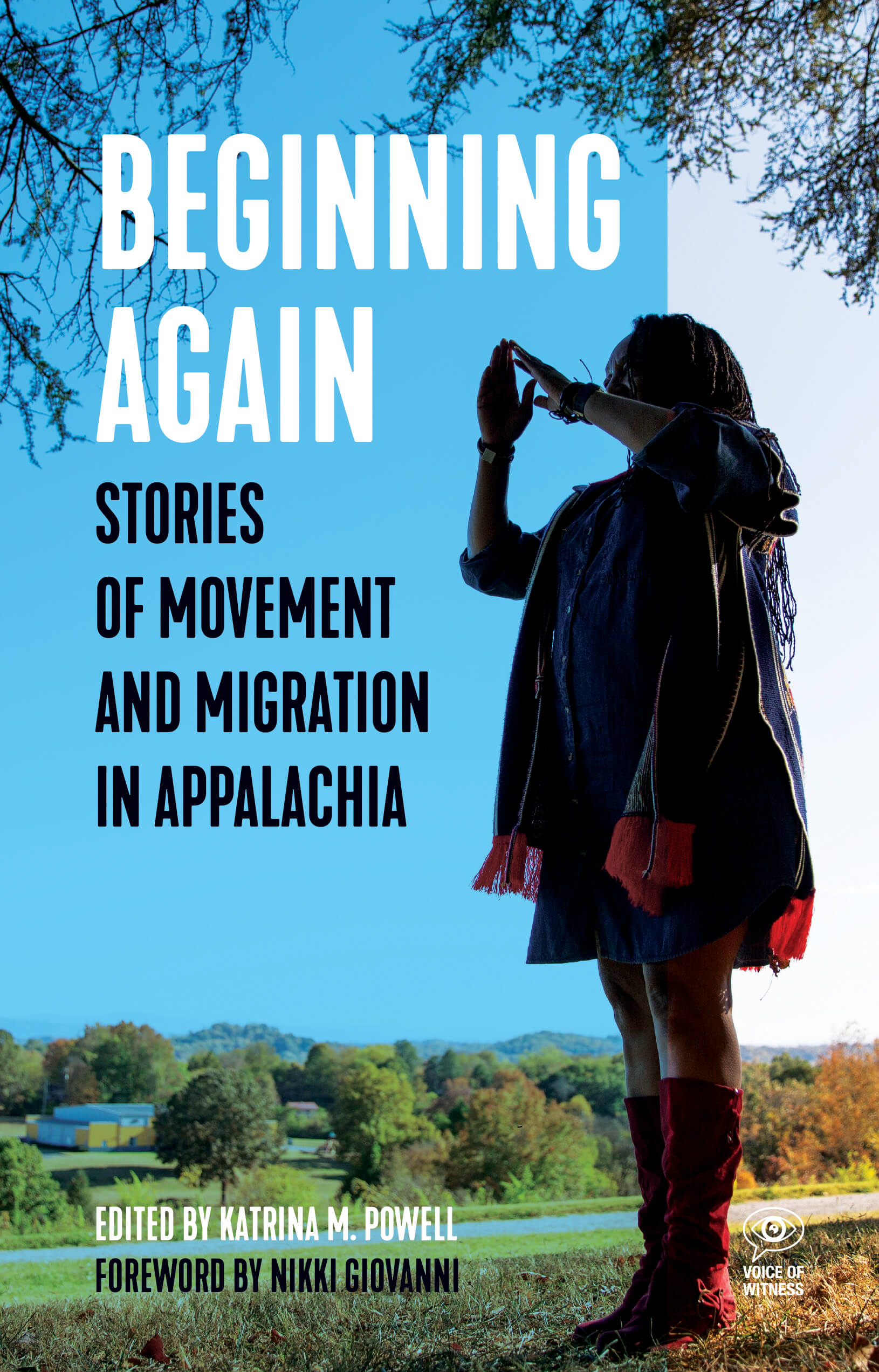

An oral history project five years in the making, Beginning Again: Stories of Movement and Migration in Appalachia brings together narratives of refugees, migrants and generations-long residents that explore complex journeys of resettlement. In their stories, Appalachia is not simply a monolithic region of white poverty and strife. It is a diverse place where belonging and connection are created despite displacement, resource extraction and inequality.

Although resettlement is not a new phenomenon in the region, media often portray the situation as a new “crisis.” Popular misunderstandings perpetuate stereotypes of refugees and migrants as a drain on resources—and Appalachians as backwards. Beginning Again adds to the growing body of works that counter damaging myths of the region and challenge one-dimensional portrayals of immigration.

Listening to these stories can help us identify the challenges of resettlement and (re)building community and work toward an Appalachia where all can thrive.

The following is an excerpt from Cindy Sierra Morales’ oral history in Beginning Again.

Cindy Sierra Morales

Born: 1995, Durango, Mexico

Interviewed in: Marion, N.C.

Healthcare Enrollment Specialist

When she was 6 years old, Cindy’s family migrated from Durango, Mexico, to Los Angeles, fleeing gang violence. After a short stay with family friends, Cindy’s family drove to Marion, N.C., where her aunt, uncle, cousins and older siblings already lived. Her parents held a variety of factory jobs, and Cindy started second grade just a few weeks after arriving. After living in the United States for 15 years, Cindy and her siblings were able to secure legal documentation through DACA.

Cindy volunteers much of her time helping multilanguage learners navigate healthcare services in the area. A leader in her community, Cindy is dedicated to helping people understand what is available to them as they seek services.

I live in Marion, N.C., but I used to live in Durango, Mexico, until I was 6. My dad ran a lumber company a couple counties over and had to leave for weeks at time. The company was passed down to him from generations of businessmen in the family.

We didn’t really struggle. We had a nice house in the city. It was a two-story house in a circle of houses. The kitchen had black-and-white tile, and I had my own bedroom. I remember the stairs in the house every single day—they spiraled. My brother taught me to ride my bike and skate on the circle street. We also had a ranch in the country where my grandmother lived. We were very fortunate.

Even though we lived in the city, my ancestral roots are very rural. My mom grew up very poor in Mexico. She had 10 siblings and they lived in a little house with no electricity or running water. She told us stories about walking a few miles to go to the well for water. My mom was able to go to school, and that’s where she met my dad.

My brother and sister, Daniel and Maria, are 10 years older than me. When I was really little, in 2000, my aunt, who already lived in the U.S., came to Mexico to visit us. When she left, she took Daniel and Maria back with her so they could go to school safely and learn English. I remember when they left. It was so weird to go into their rooms and they wouldn’t be there.

A year later, we left too, on the last day of school. When my parents picked me up on the last day of school, I got in the car, and it was all packed up. My dad said, “We’re going to North Carolina.” I knew then that we weren’t going back to our house in Durango, but I thought we were going on vacation.

I didn’t realize that we were actually moving. It wasn’t until later, when I was 15 or 16, my dad told me, “It wasn’t safe to stay in Mexico anymore.”

Even then, my parents wouldn’t tell me much—they didn’t want to scare me. But it was because we were being threatened. That’s why my sister and brother went ahead. Gang members threatened us for money. When my dad would leave our Durango house to go work in the forests, my mom would get calls from people who said, “We have your husband and if you don’t give us money, we’re going to kill him.”

My mom was tough, and she’s also smart. She and my dad had walkie-talkies. When she would get a call like this, she and Dad had signals to let her know he was okay.

Then the threats escalated. They told my dad they were going to “get you where it hurts,” meaning they would hurt my mom, me, and my siblings. So that’s why we moved to the U.S.; that’s why we picked up and left our nice house in Durango.

After we moved to the U.S. and my dad returned to Mexico periodically for his business, these threats continued. He called us from Mexico while he was there and I remember overhearing my mom say to him, “Who’s going to be there? Is it safe? Are you taking a guard?” This scared me, and I started asking more questions. But he told me not to worry about it. It was only when I got older that they told me more stories about the threats of violence.

At that point I started to grasp, even though I was young, that things weren’t the same, that we weren’t going back.

Cindy Sierra Morales

It took us a few days to get to the U.S. border. It’s about a two to three-day drive to cross into California. I was 6 when we left Mexico, so I only have blurry memories of driving to the border. Our car was piled full of stuff. I couldn’t even see out the window, and I was sitting on one little corner of the seat. I remember when we actually crossed through border control, the officer inspected our car to make sure we didn’t have anything bad in there. They took us out of the car and inspected it for drugs and some types of fruits that were illegal to bring in.

We stopped in California because my mom has lots of family there. We stayed in California for about a month, then we made our way to North Carolina. We were headed there because that’s where my aunt lived, and that’s where Daniel and Maria were.

At that point I started to grasp, even though I was young, that things weren’t the same, that we weren’t going back. We didn’t have much money at first because of the big move, and I could tell that everything was hard.

When they first arrived in North Carolina, my aunt and uncle worked picking tomatoes. There were a lot of migrant farm laborers in the area. There were some fields out in Pleasant Gardens, which is a town in McDowell County. They started by doing that until they could find a position at one of the furniture plants. My uncle found a job at the Broyhill plant, and he worked there until they shut down. My mom worked there for years too. My uncle had a similar job at Ethan Allen until he retired.

My dad got a job spraying for a pesticide company for a while. My dad would be gone all week, come home Friday, spend the weekend, and he’d leave again for a week. He did this for a little while just to get a feel of things. He had to get a little bit of income while we were here, but he was still running his lumber business in Mexico. He went back and forth from Marion to Durango.

He was risking the threats to his life to support us, and because it was a family business, he didn’t want to lose it. We all depended on him and the money from the business. We’d only see him at Christmas, sometimes Easter, sometimes during the summer. So it was just really me, my siblings, my mom, and my aunt and uncle, all living in a small house.

It was hard for me to make friends at first because of that language barrier. My parents didn’t speak English at that point, but my older cousins Edwine, Osbal and Kevin did, and they would sometimes help translate.

When my siblings graduated from high school in 2003, they went back to college in Monterrey, Mexico, for a couple years. They couldn’t go to college here because we didn’t have legal status. They didn’t graduate but came back. They were in a different city from where we lived before and didn’t tell many people—they knew how to be careful. We didn’t have legal status here at first. Then they decided to come back after we got legal status.

I was a happy child. I didn’t grow up with smaller kids around because all my cousins and my siblings were older. A lot of times, it was just me and my mom. I did great in school. I learned English that first year of school, and by third grade, I was pretty much fluent.

For us it was kind of a backward story: We had a nice house in Durango, a ranch in the country, and we went to private school. But when we got here, we moved into my aunt and uncle’s three-bedroom house. All the male cousins would whip out the blankets in the living room, and they would sleep there. I slept in a bedroom with my parents and my sister, and my aunt and uncle were with their younger son in another bedroom.

When we first got here, there weren’t a lot of services for people like us who needed financial assistance and language assistance. It was “learn as you go,” basically. For example, I needed extensive dental work as a kid. There was a place on Main Street where people without insurance could go. My sister, who was in high school, had to go with my mom to apply for the assistance, and it was embarrassing for my mom, both because of not being able to speak English and because she needed assistance.

These might seem like small things, but they’re very distressing. Ever since then, I knew that I wanted to help my community.

Cindy Sierra Morales

Another time, when I was around 13, my dad had to go to the Allstate insurance office on Main Street. While I was sitting in the waiting room, another Latino man was there, trying to get help, and the insurance agent couldn’t understand him. I knew that he was having trouble, that it was distressing for him. So even though I was a teenager, I asked him, “What do you need? I’ll translate for you.”

The guy at the desk said, “Thank you. I don’t know what I would have done if you hadn’t been here to translate.” It was hard for people to express what they needed.

These might seem like small things, but they’re very distressing. Ever since then, I knew that I wanted to help my community, especially during that transition when you don’t know anything that goes on, where things are, or how to get there.

When I was enrolled at McDowell Tech, I had to work during the months I was taking classes, so I applied for a job at the hospital. Even though I was just out of high school, I gave it a shot. I knew being bilingual might help with the growing Latino population. I got the job and first worked as a registration representative. I worked odd shifts because I was flexible, but then I had my son and needed something more set. I went from the call center to the scheduling center.

This is such a small town, so the women in the front office knew to send people who only spoke Spanish to me. They knew I was in the back office, and they’d say, “You go to see Cindy—she speaks Spanish, and she can help you.” Everybody knows you who you are here.

Word got out that I could translate, and that’s how I got this job at a resource hub working with people who are uninsured to get them connected to services—mainly primary care and anything related that comes up, like medication assistance, basic vision, dental. As the enrollment specialist, I meet with families for an initial overview and health screening. Once we get all that information, get them set up with primary care, we tell them where they need to go, who to be in touch with, to get them on a path toward a good life. We also help folks that are dealing with substance abuse to get them connected to better services for treatment and recovery.

Sometimes people don’t even know what to ask for, so we help them by asking questions about their health, their children’s health, what goods they might need, things like that. If we’d had something like that back then, things would have been so much better for my family.

My sister, my brother, and I all went to the schools here and our kids are going to the same schools. We grew up here, and we’ll stay here. We know that our roots are here.

Cindy Sierra Morales

Like my family, some of the people who are newcomers may have never had healthcare before, or mental healthcare. In the Latinx community, mental health is not talked about very much. We try to normalize asking for help for mental health, help them see that mental health disorders are a real thing.

I definitely consider myself Appalachian, even though I don’t forget where I come from. All of my main memories now are from here in North Carolina. If someone asks me where I’m from, I say I was born in Mexico, but I live in McDowell County; I’m from McDowell. To me, being Appalachian is being kind, Southern hospitality, everybody lends a hand to people in need. The county has definitely grown, and there are more people here now, especially Latino communities. It’s also grown in terms of service organizations and healthcare.

My sister, my brother and I all went to the schools here and our kids are going to the same schools. We grew up here, and we’ll stay here. We know that our roots are here. I don’t see us moving anywhere. Marion has everything for us.

My dreams for my children are the same as those my parents had for me… I think I’ve fulfilled my parents’ dreams.

Cindy Sierra Morales

Some of the people I work with are really struggling, and I feel guilty at the end of the day. Maybe it’s not guilt, but I’m very conscious of things people are dealing with. There’s still so much that needs to be done.

My dreams for my children are the same as those my parents had for me. I hope they fulfill their dreams as Americans, but I also want them to know where I came from and what we went through to get here. My son has more privilege than I had as a child, but I want him to be grounded and humble and to give back as well. He’s a very kindhearted little boy. He’s got a huge heart. Talking about my family reminds me of this quote: “You are the answer to the dreams of your ancestors.”

I think I’ve fulfilled my parents’ dreams. They wanted us to have good jobs and give back to our community. I know my mom is happy about where I am today. She has said that what I do, she wishes someone would have done that for our family.

Up next:

U.S. democracy is at a dangerous inflection point—from the demise of abortion rights, to a lack of pay equity and parental leave, to skyrocketing maternal mortality, and attacks on trans health. Left unchecked, these crises will lead to wider gaps in political participation and representation. For 50 years, Ms. has been forging feminist journalism—reporting, rebelling and truth-telling from the front-lines, championing the Equal Rights Amendment, and centering the stories of those most impacted. With all that’s at stake for equality, we are redoubling our commitment for the next 50 years. In turn, we need your help, Support Ms. today with a donation—any amount that is meaningful to you. For as little as $5 each month, you’ll receive the print magazine along with our e-newsletters, action alerts, and invitations to Ms. Studios events and podcasts. We are grateful for your loyalty and ferocity.