Solicitor General Prelogar also strongly backs the trans-inclusive sex discrimination definition in the Title IX education rule, quoting repeatedly from Justice Gorsuch.

This column was originally published on Law Dork.

On Monday, the Justice Department went to the U.S. Supreme Court in defense of the Biden administration’s new Title IX sex discrimination rule that includes transgender protections—arguing strongly that the logic of the rule is “compelled” by a recent high Court ruling.

The rule, issued under Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972, is set to go into effect on Aug. 1. In part, it defines sex discrimination as including discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity. This, the Biden administration has argued, followed from the Supreme Court’s 2020 ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County, where Justice Neil Gorsuch held for a 6-3 Court that the sex discrimination ban in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 includes discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity.

Despite the simple logic behind such an argument—which I’ve discussed previously—Republican judicial appointees have blocked the rule in 15 states over the past five weeks, as well as in schools attended by members of two far-right organizations and the children of members of a third far-right group.

In a pair of Monday filings, the Justice Department asked the justices to allow the Education Department to partially enforce the new rule during appeals in 10 states where a pair of injunctions are blocking the entirety of the 423-page rule from being enforced.

Responses were requested to the Justice Department’s applications by noon on Friday—giving the Supreme Court plenty of time to issue orders before the rule is to go into effect on Aug. 1.

The injunctions at issue in those two lawsuits cover Idaho, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Montana, Ohio, Tennessee, Virginia and West Virginia.

The requests ask the justices to limit the injunctions while appeals are being heard so that the injunctions will only block two provisions—the ones that the plaintiffs argued about in their lawsuits. DOJ is not giving up on those provisions; they will still argue over them on appeal. But, at the Supreme Court on Monday, the department argued that the injunctions are overbroad because they block much more than those two provisions.

Similar efforts to limit the injunctions during appeals were already denied by two federal appeals courts, both on 2-1 votes, which is why Monday’s filings were only in those cases.

The other five states in which the rule is enjoined are Alaska, Kansas, Texas, Utah and Wyoming.

As Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar put it in the Monday filings seeking partial stays of the injunctions in two of the cases, “Respondents have not challenged the vast majority of th[e] changes. Instead, they object to three discrete provisions of the Rule related to discrimination against transgender individuals.”

Prelogar noted that, in the lawsuits at issue, the states and others suing over the rule have only actually challenged the provision defining “sex discrimination,” a section relating to “sex-separated facilities,” and a section discussing “hostile-environment harassment.” All three sections, she explained, contain language that would provide protections for trans students.

Prelogar told the justices Monday in no uncertain terms that the facilities opposition is because the states and groups “want to prohibit transgender individuals from using sex-separated facilities that align with their gender identity” and the opposition to the hostile-environment harassment provision is because “they fear that it could require students and faculty to refer to transgender individuals using pronouns that correspond to individuals’ gender identity.”

Nonetheless, Prelogar wrote, “Those provisions raise important issues that will be litigated on appeal and that may well require this Court’s resolution in the ordinary course. But the government has not asked the courts to address those provisions in an emergency posture.”

In other words, DOJ is going to litigate those two provisions in the lower courts before asking the Supreme Court to address them.

But, as to the definitional provision of the rule, as well as the other 400-some pages of the rule, DOJ argued on Monday that injunctions are inappropriate—and so the injunctions’ inclusion of anything beyond those two provisions should be stayed.

The department made the Supreme Court’s action earlier this year in Labrador v. Poe—granting a partial stay of a lower court injunction blocking Idaho’s ban on gender-affirming medical care for minors—central to its argument. There, the high Court’s majority held that the scope of that injunction—a statewide injunction of the entire law—was inappropriate given the plaintiffs and their claims.

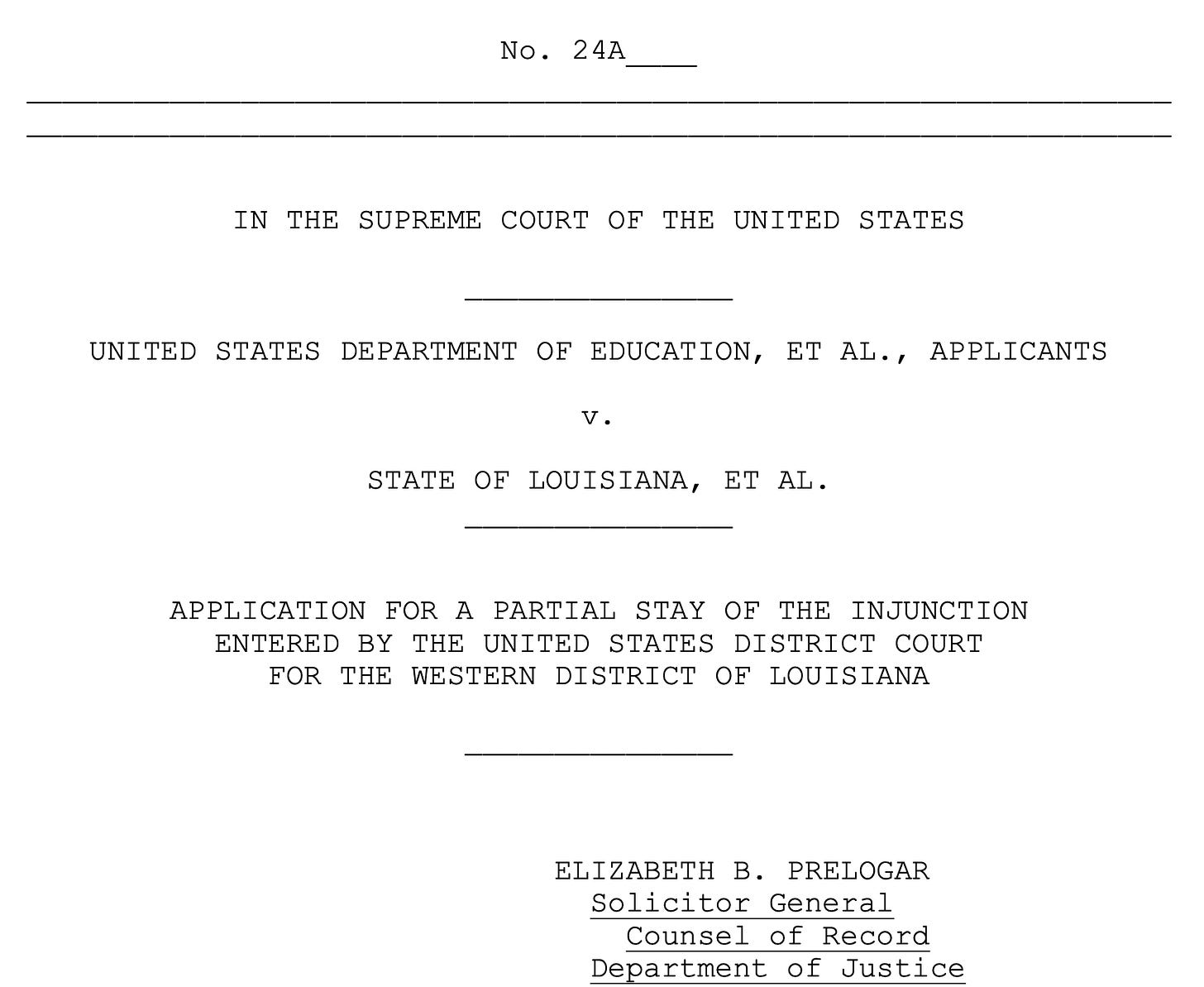

Here, in asking the court to narrow the Title IX rule injunctions, Prelogar quoted repeatedly from Gorsuch’s concurring opinion in Labrador, in which he had explained why he believed the scope of the injunction was inappropriate there, to begin her argument:

![Just a few months ago, this Court granted a partial stay because a district court had entered a sweeping preliminary in- 2 junction that flouted the fundamental principle that equitable relief “must not be ‘more burdensome to the defendant than neces- sary to redress’ the plaintiff’s injuries.” Labrador v. Poe, 144 S. Ct. 921, 927 (2024) (Gorsuch, J., concurring) (brackets and citation omitted). Several Justices warned that “[l]ower courts would be wise to take heed” of that reminder about the limits on their equitable powers. Ibid. The lower courts here ignored that warning, and this Court’s intervention is again needed. Just a few months ago, this Court granted a partial stay because a district court had entered a sweeping preliminary in- 2 junction that flouted the fundamental principle that equitable relief “must not be ‘more burdensome to the defendant than neces- sary to redress’ the plaintiff’s injuries.” Labrador v. Poe, 144 S. Ct. 921, 927 (2024) (Gorsuch, J., concurring) (brackets and citation omitted). Several Justices warned that “[l]ower courts would be wise to take heed” of that reminder about the limits on their equitable powers. Ibid. The lower courts here ignored that warning, and this Court’s intervention is again needed.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb85e412c-112e-44ef-a4c4-7ad09325369c_1368x1136.png)

She later argued that “the district court plainly erred in enjoining dozens of provisions that respondents have not challenged and that the court did not find likely unlawful. Like the injunction in Labrador, that sweeping relief ignores the fundamental principle that equitable relief must be tailored to match the plaintiffs’ injuries and legal claims.“

Additionally, Prelogar argued that the injunction against enforcement of the definitional provision had a similar problem. Although it was challenged in the lawsuit, she argued that it should not be enjoined during appeals because “respondents have never suggested that they wish to violate the [definition] provision … by punishing or excluding transgender students ‘simply for being transgender,’” as Bostock addressed, or “by otherwise engaging in gender-identity discrimination outside the limited contexts governed by” the facilities and hostile-environment harassment sections.

In other words, DOJ argued that an injunction against enforcing the definition provision of the Title IX rule is inappropriate because the states and groups claim no injuries from that definition beyond those relating to the other two provisions—enforcement of which would remain enjoined during the appeals.

Regardless of that—and this is key—Prelogar argued that “inclusion of gender-identity discrimination is compelled by a straightforward application of this Court’s decision in Bostock.“

This is the crux of the matter—and it’s important that Prelogar made that clear from these first two filings at the high Court relating to the Title IX rule …. because there certainly will be more.

Up next:

U.S. democracy is at a dangerous inflection point—from the demise of abortion rights, to a lack of pay equity and parental leave, to skyrocketing maternal mortality, and attacks on trans health. Left unchecked, these crises will lead to wider gaps in political participation and representation. For 50 years, Ms. has been forging feminist journalism—reporting, rebelling and truth-telling from the front-lines, championing the Equal Rights Amendment, and centering the stories of those most impacted. With all that’s at stake for equality, we are redoubling our commitment for the next 50 years. In turn, we need your help, Support Ms. today with a donation—any amount that is meaningful to you. For as little as $5 each month, you’ll receive the print magazine along with our e-newsletters, action alerts, and invitations to Ms. Studios events and podcasts. We are grateful for your loyalty and ferocity.